administering COVID-19 shots at mass vaccination events

just those 20 to 60 seconds you spend on the jab, based on having jabbed 1000’s of arms at multiple vaccination sites in multiple states

At COVID-19 vaccination events, each vaccinator might inject hundreds of arms per day (sometimes 1 arm per minute, sometimes one every 20 seconds, depending on the site). At such events, I typically give more IM (intramuscular) injections in 10 minutes than I gave in a full year as a hospital bedside nurse (where I’d do about 1 IM injection per month).

Observing the many vaccinators around me (mostly nurses or emergency workers), I see that no two people vaccinate in exactly the same way. When I ask, “why do you do it that way?” the answer is usually “that’s how I was taught, but I’ve made adjustments for the rapid Covid pace”.

All this variety in technique has left me wondering: Are we doing this correctly? Has the non-conformity of training, and the shortcuts based on expediency, led to mistakes that could affect lives?

So, I’ve been going through the published research about IM injections—none of which says “here’s the best way to vaccinate at a fast-moving COVID site”—and doing my best to cram as much of that evidence as possible into my real-world practice.

What follows is how, and why, I perform COVID-19 vaccine injections at a 2021 mass-vaccination site (with modifications based on the protocols of each site). I don’t claim that this is the only correct way to do everything, but it is what I do and I’m doing my best. (If it turns out that I’m terribly wrong about anything, and publishing this leads to someone correcting me, then it will have all been worthwhile.)

1) The main thing: get the vaccine in the muscle and keep it there

The vaccinator’s primary and secondary tasks are to

Get the vaccine into the muscle

Keep the vaccine in the muscle

WHY? All COVID-19 vaccines have been tested and approved using IM injections. That means we know that when the vaccine is in the muscle, it works. We do not know if these vaccines work when they’re instead injected into fat, subQ or subdermal tissue, or into a vein. Maybe those other routes work, maybe they don’t—but the point is that we don’t know.

There are plenty of reasons to assume that the muscle is the right place for the vaccines (good blood supply for dispersion, but not too good; good degradation of vaccines, but not too good; quick recruitment of immune cells; lower chance of local granulomas and fibrous irritation), and so it makes sense to use the muscle. With these early COVID-19 vaccines (Pfizer and Moderna) it’s also important to know that they’re not stable for long when not refrigerated; so, if they’re injected into the fat they may stay there for a while, warming, degrading, and becoming ineffective before they make their way into the patient’s other tissues. But all that’s just speculation. The real reason to use the muscle is because that is what has been tested and is known to work.

1a) Why might the vaccine not get into the muscle? Because the vaccinator missed.

It’s easy to miss the muscle.

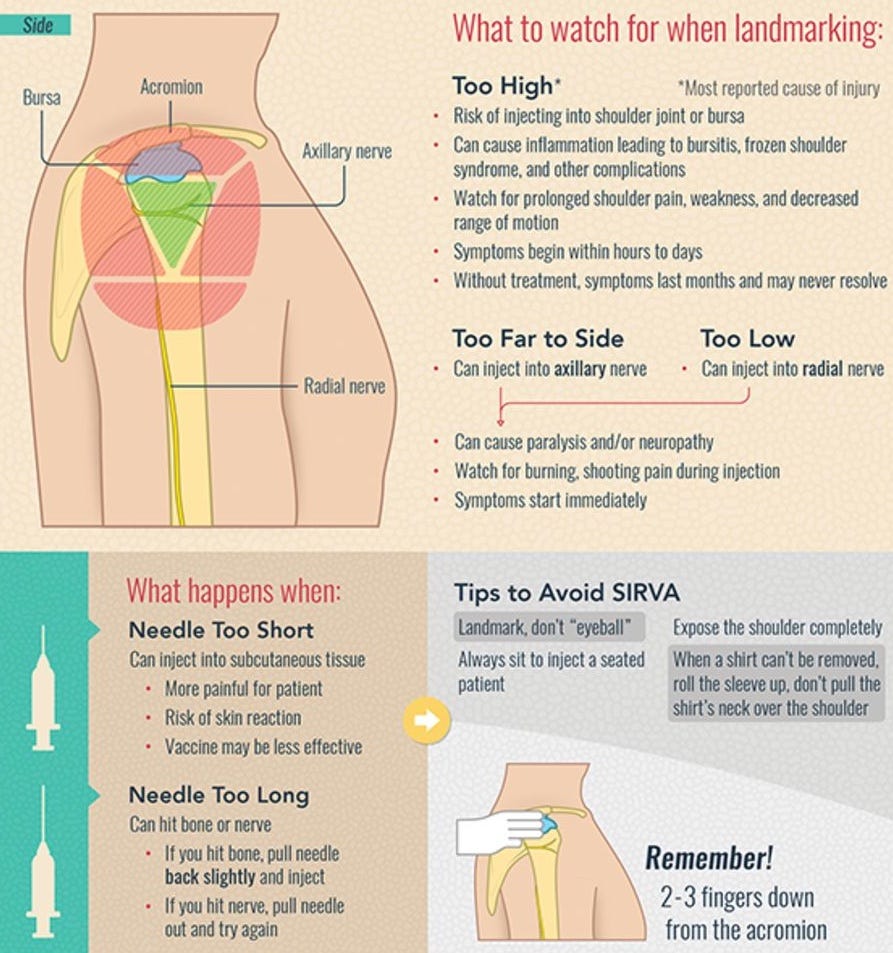

First, you have to find the deltoid muscle, then target an area on the skin near the middle of that muscle. This is important not just get the vaccine where it belongs (as already discussed) but also to avoid nerve or bursa injury. In a fast-moving clinic, it’s easy to think you can just eyeball this and get it right, but it’s worth taking an extra second to landmark the site with your fingers. This figure is a good summary of the landmarking and risk issues: 1

Second, you need to get the right depth, beyond the skin and fat and into the muscle. Ideally, you are provided multiple needle lengths as per CDC guidance [CC] but in reality, at a fast-moving clinic site you might not have a lot of choices. If the provided needle is too long for a thin arm, estimate how deep to go instead of pushing the needle all the way in. And if the needle is a little short for a big arm, you may need to emphasize the z-track (see below) and push the needle in a little harder. Do your best. 2

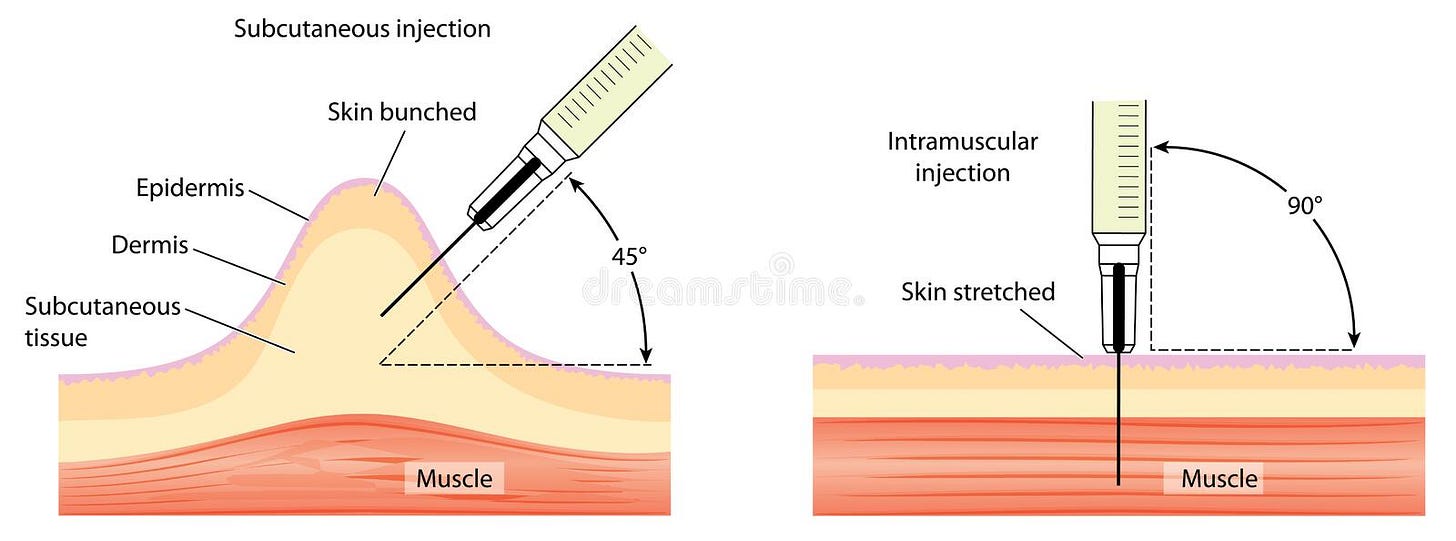

The most common depth error I see (again and again at clinics, in news photos, and on TV) is simply the vaccinator who squeezes up a lot of the patient’s arm before injecting. This squeeze bunches up a lot of skin and fat under the needle, making it unlikely that the needle is long enough to reach through that pinched-up skin and fat and reach the muscle. The vaccine needs to reach the muscle. Pinching is for subQ injections, not IM, so I support #DoNotSqueezeMyArm (with the one exception of thin or aging arms with small muscles, where you may need to bunch up the deltoid muscle to make it thicker). 3

1b) Why might the vaccine not stay in the muscle? It’s debatable.

Most sources will say that if you push medication into a muscle too fast, it won’t all be absorbed by the muscle because some of the medication will flash back out (think of plunging a clogged toilet very quickly, while you’re wearing your best white clothes, and what might come splashing back out). Also, if you go straight in with the needle, the medication has that needle-made hole to come straight back out again, and so a z-track method is recommended.

However, others believe those effects are only relevant for large-volume IM injections (e.g., 3ml) and not for low-volume (0.3ml - 0.5ml) Covid vaccines. And there are mixed results about whether injecting quickly causes less pain (although by quickly they usually mean the recommended 10-second/mL versus something even slower).

What do I think? I’ve been fortunate during these high-volume events to be able to try different speeds, and z-track versus straight-in. In my admittedly anecdotal experimentation, I believe I have seen some tiny leakage from not doing the z-track method, and I have not witnessed extra patient pain when I inject at the recommended 10-second/mL rate (which translates to 3 to 5 seconds for Covid vaccines) and even leave the needle in a few extra seconds. So, that’s what I’ve settled on: z-track, 3 to 5 seconds to push, and leave it in an extra couple of seconds. 4 5

A clever vaccine partner to taugh me a variant of the z-track techniques that I think works very well in the fast-paced hectic world of a vaccination mega-event. I’m calling it the “Adjavent Squeeze” technique, as demonstrated in this footnote: 6

By the way, most considered opinion is that immediate massaging may encourage vaccine to leak from the muscle, and so I don’t massage the arm after injecting (before is OK, as part of the alcohol rub, because people seem to find comfort in that).

(Finally, if anyone can find evidence that a tense muscle is less likely than a relaxed muscle to absorb an injection, I’d like to hear about it. In my experience, a relaxed muscle is a lot less stressful for the patient and for me, it hurts less, and it’s easier to push the needle in. Improved vaccine absorption would be yet another reason to encourage people to relax their arm.)

2) Safety

2a) Hand Hygiene & gloves, gloves, gloves, gloves

The current CDC guidelines are that gloves are not required for most vaccinators as long as hand hygiene is performed between patients. If gloves are worn, then they should be removed after each patient, followed by hand hygiene and a new pair of gloves [2]. Proper hand hygiene, in these clinical situations, should be a dime-sized dab of alcohol-based hand sanitizer rubbed thoroughly over all hand surfaces for 20 or 30 seconds until it is dry. 7

Following the above guidelines is nearly impossible at a large and fast vaccination event, for many reasons. 1) I’ve yet to hear of a site that does not require gloves, and so gloves will be used. 2) There is not enough time between patients to take off gloves, rub in a dime-sized dab of sanitizer for the 30 seconds it takes to dry before putting on a new pair of gloves. 3) Extremely few people can put on new gloves when their hands are wet from sanitizer or sweat—I’ve seen a few who can perform this trick, but I have no idea how they do it.

Since the guidelines are impossible in this real world, you have to skimp on something.

The one part of the guidelines I personally do not think you should skimp on is to use hand sanitizer (on something) between touching patients. But many vaccinators do skip the hand sanitizer, believing that changing one or two gloves is enough. NO! A typical glove has not only been sitting around in not-especially-sterile conditions, but it has holes in it that are like swiss cheese to something the size of a virus. Only a sanitizer and rubbing and time has a chance of destroying a virus between patient contacts.

CDC’s says that when gloves are limited it is OK to keep gloves on more often, and clean them directly with hand sanitizer just as you would your hands, until they show signs of degradation or being soiled. Most gloves appear to last for many cleanings and to be more sanitary after cleaning than hands. As an environmentalist, I would argue that we should be in a glove-limited situation. So if you want to use hand sanitizer on a glove between patients, I won’t turn you in, but not everyone is ready for this step yet. 8

Whatever you skimp on, wearing two pairs of gloves will probably help. It’s much easier for most people to replace just the outer gloves than to remove a sole pair of gloves and put on new gloves over bare hands. In the double-glove case, the something you wipe hand-sanitizer on, and attempt to rub until dry, will be your inner gloves. (Some people are careful to touch the patient with only one hand, so they only need to frequently change that one patient-touching hand—saves time if you think you’re good enough.)

2b) Arm Hygiene

You’re going to swab the skin with an alcohol wipe before injection (despite a surprising lack of evidence that this helps). I’ve found it’s best to do this first thing because it gives time for the alcohol to dry (injecting through wet alcohol stings), and it’s a good time to talk to the patient, calm them, get their arm loose, and tell them what’s coming up. 9 (If you’re using the one-patient-touching hand technique mentioned in the previous paragraph, then that’s the hand to wipe with.)

2c) Syringe & Needle

Check that the syringe is on firmly (it’s an unpleasant experience for everyone to have that cap break off in the middle of an injection), and that the right amount of vaccine is in the syringe (some can easily be pushed out in all the hubbub of a clinic). Do this on every syringe you use.

2d) Prepare for the unexpected

After hundreds of injections, it’s easy to become complacent. You never know if this is the confused patient who will suddenly jerk back when they notice someone is stabbing them. Also, I haven’t had it happen with me, yet, but sometimes a person will just right-out faint.

2e) Chaos

There’s a lot going on. You don’t want needle sticks. Keep track of your needle. Put it in something safe first thing (preferably in safety container right next to you, or in whatever next-best contraption you have 10) before handling anything else. Yes, if an arm has to bleed a few drops while you get that needle safe, let it bleed!

3) Preparing the patient

Your vaccinatee is probably tense and nervous. Be calm. Tell them to be calm (alcohol wipe is a good time for this). If their arm is loose (“let it hang like a floppy rope”), the alcohol is dry, and you can ask them to breath deeply or provide any other distraction, then it’s almost never going to hurt. Sometimes I throw in a joke, a question, or a compliment just as the needle is about to go in. I had one situation with a check-in partner where he would always ask them a question a split second before my injection, and they never felt a thing.

4) Conclusion

Mandatory (don’t skimp on these):

locate the deltoid and including the depth

perform hand hygiene on something

check the syringe and needle

safely store the needle immediately after injection,

If you’re still bored, there’s a lot more information to read about those few seconds spent giving an IM injection. [11]

Deltoid landmarking and risks related to wrong placement or depth:

Shoulder injury related to vaccine administration and other injection site events

SIRVA (Shoulder Injury Related to Vaccine Administration) and treatment

These images demonstrate where the central portion of the deltoid is (the triangle), and a good target for the injection (the circle).

CDC guidelines for vaccine administration:

on the importance of #DoNotSqueezeMyArm:

Doctor Sounds Alarm on How to Properly Inject COVID-19 Vaccine [1] [2] - TV News Reports

Evidence calls for practice change in intramuscular injection techniques

This image demonstrates SubQ (skin bunched) vs IM (skin stretched)

Bunching our volunteer’s arm creates at least an inch of extra tissue to tunnel through before the needle reaches the muscle. A 1-inch needle won’t make it into the muscle.

z-track, skin-stretching (and more)

injection speed (and more)

The Adjacent Squeeze z-track technique. The typical z-track involves pulling some skin aside or stretching the skin between one’s fingers. In vaccine clinics I’ve found both of these problematic due to positioning (car, standing, twisting), rapidity, and because I’m often wearing ill-fitting gloves quickly applied. What happened too often is I either had a poor grip against the patient’s skin, or the patient thought I was pushing, moving, or repositioning them.

For example, in this picture, demonstrating how the skin around the target circle can be stretched, I notice that I had to put my other hand the our volunteer’s right shoulder to prevent her from being pushed away from me.

In the Adjacent Squeeze z-track technique, you grab a bunch of skin adjacent to your injection target and pull it to the side. This both stretches the skin tight over the muscle, pulls the skin aside for best z-tracking, and gives you a good hold on the patient’s arm. I love it.

The one bit of art in using the Adjacent Squeeze is to note that when you pull the skin aside, you will no longer be aiming for where that target circle is, but instead for where the circle was, because you have pulled the circle aside.

This series of images shows how when the skin is pulled forward (but not the muscle), the syringe (here represented by a black marker) is aimed where the circle use to be (and where the muscle still is), so that when the skin is released it will cover up the muscle and prevent leakage, as a good z-track should.

Hand sanitizer on gloves