While working for a few years as a bedside hospital nurse1, I developed a set of paper forms (commonly called “brains”) and techniques that I used throughout each shift to take care of my patients, and to document what should to be done and what was done (and when), to the best of my imperfect ability.

In this post, I will describe my methodology. If you, like me, have an imperfect memory, work overburdened shifts, must make do with cumbersome access to crappy electronic health records, and yet, despite all this, want to be accurate and honest in providing your best care to every patient, you may find some of these tools and techniques useful.

Please use and modify what you can (everybody is different) and discard the rest.

What are Nursing Brains (aka, Brain Sheets, Handoff Report Sheets)?

It has long been common for nurses to keep track of each patient’s information on paper they carry around with them. Even with the ubiquity of electronic health records (EHR), where everything is ultimately referenced and recorded, nearly every nurse is constantly referring to and writing on some piece of paper. Nurses use paper instead of the computer either because that’s how it’s always been done, or because the computers are much too cumbersome and slow for the fast-paced action needed to care for multiple patients in multiple rooms simultaneously. When you rush into your patient’s room because you hear them cry out in pain, there’s just not time in the moment to wheel in a computer, log in, and look up information about that patient’s status. And there’s likely not time at the moment (because another urgent matter is going on with another patient) to log your every intervention in real time. So, nurses rely on a quick glance on a sheet of paper and maybe jotting down a bit of information to be recorded in the computer later.

Some nurses believe they can rely on memory, instead of writing it down, for patient condition, history, and interventions scheduled and completed. I believe that the number of nurses whose memories can accurately store and recall all this information mentally is exceedingly small (although those very few who can do it are amazing). Many believe they can do this mental task of keeping their “brain” in their actual brain, but they’re almost all wrong and so are blissfully unaware of the many mistakes they’re making. So, writing on paper is necessary. This paper is usually called a Nursing Brain, Brain Sheet, or Handoff Report. I’ll call them “Brains” because, at least in my case, they compensate for the deficiencies of my own decrepit mental organ.

Without my brains, I don’t know how I could have made it through a shift taking good care of my patients.2

Background: What a nursing shift looks like

To best understand this post, you’ll need a quick overview of what happens during each shift of a hospital bedside nurse (particularly critical care, such as med-surge, tele, stepdown, etc…). In case you’ve never had such a job, it goes something like this (some hospitals do this better, I assume some do it worse):3

You clock in no sooner than a few minutes before your shift—in my hospitals this was 7 minutes to get prepared before the critically-ill patients are yours to care for (assuming you’ve already gotten ready, got your supplies, put your things in a locker, put your lunch in the refrigerator, etc., before you clocked in). First, you spend a couple of minutes getting your list of patients for the shift. The number of patients varies based on acuity, unit, and hospital. For instance, in my recent med-surge (medical-surgical) job, I’d have between 3 and 7 patients, but typically about 5.

Now you have the few minutes until shift begins to log in to the computer and get acquainted with your patients. In my shifts, that meant I usually had 5 minutes to learn about 5 patients—their histories, doctors, medications, and orders—and scribble things down on my brains.

If you think one minute to learn about each patient is crazy little time, you’re correct. It’s not enough time, especially with the computer system interface being archaic and very poorly designed. So, it’s not uncommon for nurses to come in much earlier than those 7 minutes to gather this important knowledge, even though they’re not on the clock and not getting paid. Possibly worse: doing this patient work when off the clock may be a violation of labor, OSHA, and HIPAA laws, and some argue that it it could be grounds for losing your license. Still, many nurses do come in early, doing this work off-the-clock in order to provide the best care possible, because they care more about their patients than laws or their employer’s miserly rules. It sucks!

Next there might be a huddle where nearly everyone is together for a few minutes to get caught up with the latest unit status and concerns.

Then come the handoffs. Handoffs are where the nurse who previously cared for your patient is passing on the responsibility of that care to you. If you’re lucky, you have a few minutes to hear about the patient, be introduced, hear history, plans, concerns, and full status. Watching these handoffs, you’ll usually see the outgoing nurse fast-reading from their notes while the incoming nurse is hurriedly scribbling on their own notes. These notes (i.e. brains) are very important, because that one-minute-per-patient preparation time before the shift is totally inadequate, and so most of the important care information may happen verbally during these handoffs—the previous nurse to you, then you to the next nurse, and so on, shift after shift.

If you think relying on hurried verbal handoffs and scribbling is a terrible way to exchange important care information, you’re correct. If you’ve every played the game of telephone you will not be surprised to learn that essential information is frequently lost, and misinformation frequently added, compounding at every handoff.4

For the next hours of your 8 or 12 hour shift, until the next nurse comes on, you then care for that patient. You must make sure their unique-per-patient orders are followed, their meds are checked for safety and given on time, they’re assessed with needed frequency, their inputs and outputs are measured, and on and on… so many rules… and everything must, eventually, be accurately documented in the computer. Oh, and you have schedule time to take your required break.5

Guiding Principles behind My Brains

My brains try to overcome these three sucky problems:

Memory Sucks. Don’t rely on memory for anything. As was said so often said on that TV show, House, R.N. : “Everybody Forgets” (or maybe House said something different, I don’t remember).

EHRs suck. The computer isn’t at hand, or it takes too long to log-in and enter data. In the thick of it, you only have a moment to glance at information and another moment to jot something down. So quick-access data must be stored on the brain.

Two hands suck. While your two hands are busy taking care of your patient, those same two hands can’t also be managing paper or computers. Until genetically modified humans get more hands, the brains have to be out of the way as much as possible, but still quickly accessible, read- and write-able, and difficult to lose.

With a proper science-fiction computer interface, AI, and genetic human modification, items 2 & 3 will be solved, and eventually even item 1. But that feels a long way off. The world needs a nurse with experience in engineering and computer science. Hmmmm… I wonder who that could be…

Brain Paper: Size & Weight

If there is one thing especially unique about my brains, it is the size & weight of the paper I use. Seriously.

The standard 8½ x 11 inch (A4) letter-size paper is too big to fit in a nurse’s pocket without folding, and too floppy to write directly on without holding against a hard, flat surface. This leads many nurses to either bring a clipboard with them everywhere, just to support the floppy paper, or to be frequently putting their paper down on various services (which are seldom in a convenient, germ-free place).

The thickness and sturdiness of paper is measured in bond weight. Standard flimsy letter paper is 20 lb. I use 80 or 100 lb, which is the thickness of card stock. With this thick paper I can write directly on my brains, as I hold them in one hand, without the need of any backing surface.

For me, the thicker the better, as long as it is very white and has a good writing surface, and so I would like to be using 100 lb. thick cardstock (100 lb example @ amazon), but my printer struggles feeding that size through its gears, so I’ve been using 80 lb (80 lb example @ amazon).

I then cut these thick 8½ x 11 inch sheets in half, giving two 5½ x 8½ inch sheets. 5½ x 8½ is just the right size to fit in the side pants pocket of my scrubs. With a few sturdy brains in that pocket, I can quickly slide them out, read & write on them, and slide them back again without missing a step.

Patient Brain: The patient at a glance

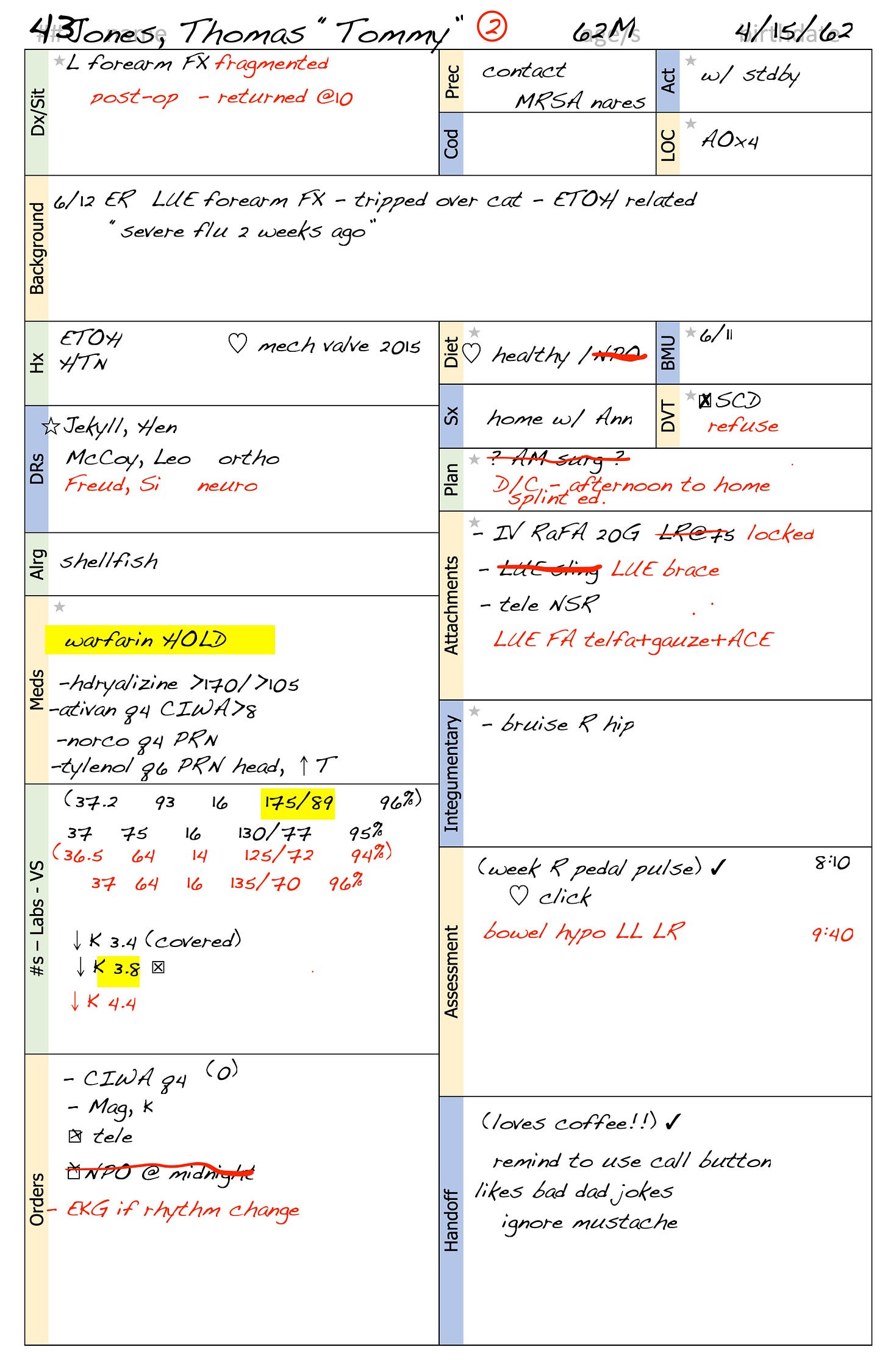

The least unique thing about my brains is the single half-page I keep on each patient, which looks like this before I’ve added information (see Additional Resources section below for ways to print this document for yourself, and for links to many other brain styles):

And might look like this after I’ve been using it for half a shift (if my handwriting were legible):

At the start of the shift, in those few minutes before handoff, I fill in a few of the basic items about this patient from the computer, such as identifying information, allergies, code status, providers, most-recent vitals, and when they arrived. If there’s a few extra seconds (which often there is not) I can look for interesting orders, when they may have had interventions, diet, and precautions. More of the information is filled in during the handoff, and the rest is filled in just as quickly as I have time during the shift.

This Patient Brain will also be my primary prompting tool when I handoff this patient to the next nurse during shift change. I will pass on the information from this sheet that the next nurse needs to know.

Notes about Tommy’s Brain

I hope much of this is self-explanatory, and if you’re a nurse you probably have a lot of your own quirks for how you record stuff. Here are a few notes on my own quirks used for Tommy’s Brain:

I only write things that are most relevant to know, quickly, for this patient, and that are not within normal limits. For example: in the “code” section I usually don’t have anything unless they’re DNR or have special instructions; in “assessment” I’m not going to write about their lung sounds unless they’re not clear, or were previously not clear, or the patient is in for a lung issue; in “order” I don’t write every goddamn order of the hundreds that exist for every patient, and so on.

The is the second shift I’ve had Tommy (i.e., yesterday I handed him off to a nurse who today has handed him back to me). So, I reuse yesterday’s brain, but use a different colored pen (red), and alter whatever has changed. This saves a lot of time and helps me provided even better care for Tommy today than I did yesterday.6

I put items in parenthesis if I consider them hearsay and so haven’t verified it myself. I use these parentheses a lot of times when I get information from another nurse in handoff that I haven’t yet verified on my own, especially if it’s a nurse I haven’t learned to trust7. For example, in “Assessment” I have “(week R pedal pulse)” because I heard it in handoff but hadn’t checked yet (then I added a ✓).

I use yellow highlighter for when I think something is very important to report or remain aware of, such as Tommy’s BP that was worryingly high before my first shift and that I re-checked first thing, or the low potassium that needed to be covered, especially in preparation for possible surgery.

I use ☐ for items I need to do (and often have them on the timesheet, below) and change to 🗹 when they’re completed.

The back of Tommy’s Brain – empty and open for anything

The back side of each of these brains is blank (I don’t bother to show that here, because we all know what blank looks like). I often use that for scratch or any random bit of information about this patient. For example, I might write orders given by a Dr over the phone, before I transfer them to the EHR. Or I may use it for scratch in calculating dosage. Or the brother’s phone number. Etc…

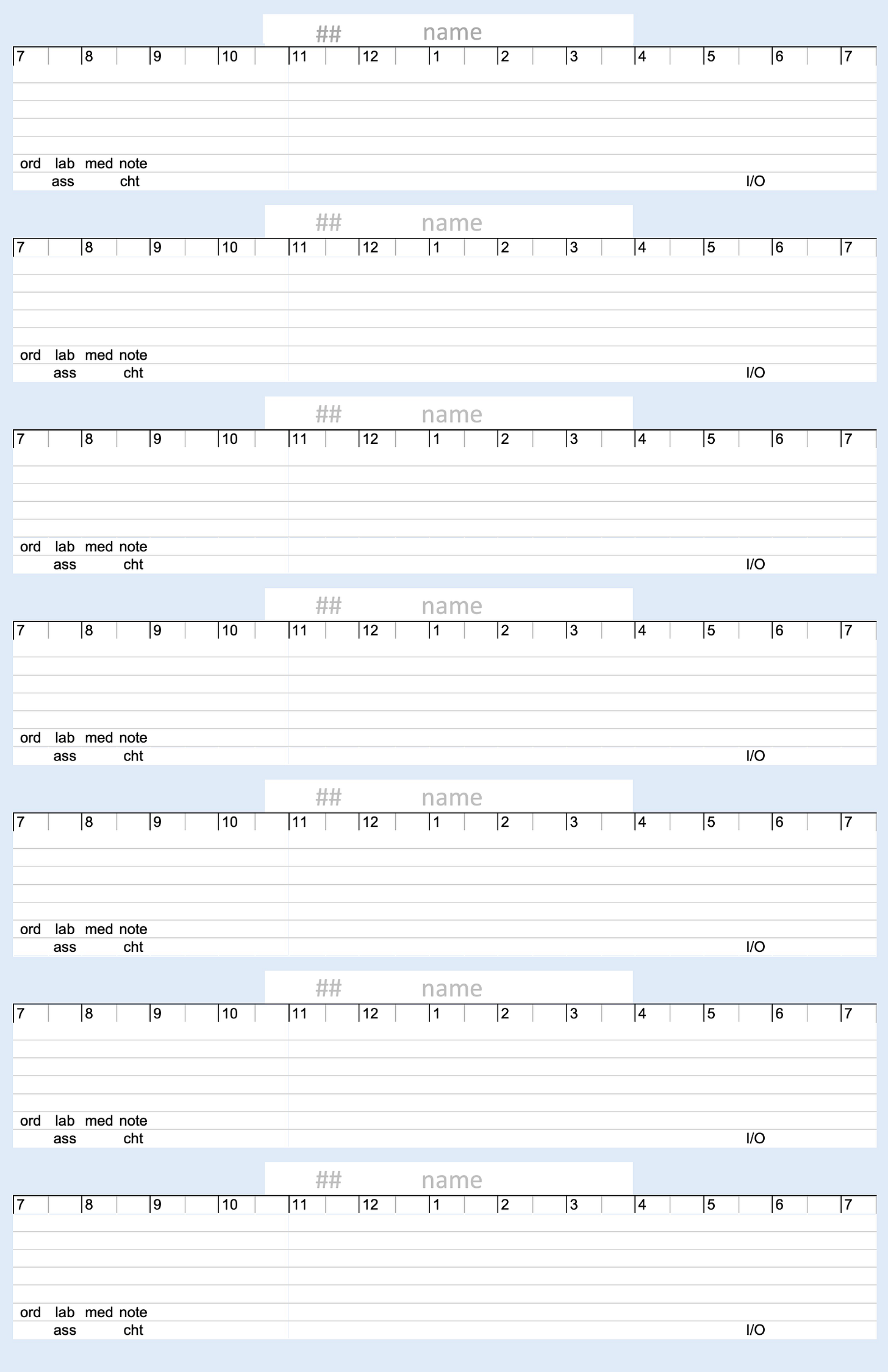

Time Brain: The shift at a glance

The Time Brain is the most important 5½ x 8½ inch document of my shift, showing me in one stiff half-page what things needed to be done and when they were done. I am nearly constantly looking at my Time Brain to see what is due now, scratching TODOs on it, marking things off. I’d be lost without this little page.

The blank Time Brain looks like this (see Additional Resources section below for ways to print this document for yourself):

And might look like this after I’ve been using it all shift (if my handwriting were legible). Actually, I wrote less on this example than would happen in a true busy shift, just to make it legible for discussion:

Notes about this Time Brain example

Some notes on ways I manage time with this sheet:

I put items closer to the top time marks when they’re more important, and more important that they be done at a certain time. For example, with LouLou in 42, I wrote PCA every four hours very close to the top line to remind me to assess and log this important information very close to four hours apart. But CHG, where needed, is written much lower because it’s not super important exactly when that happens. You can also see that Flo in 45 had a few non-critical items she was asking for at the start of shift.

When an item is completed, I draw a line to the time it happened (depending on how exact timing must be), and scratch it out when it has been entered into the EHR (when HER logging is required).

The last block here has no patient associated with it. So, there I’m just adding a few things I need to remember to do that aren’t associated with any particular patient. (Am I really going to have time to fix the computer in the break room? I doubt it.)

Notice that Jamar in 52 has been in OR since my shift started. Sweeeeeet! Every time I look at this timesheet, I’m reminded that I don’t have to check on Jamar just now. Sweeeeeet! But it looks like I’ve used this as an excuse to neglect reading up as much as I should about Jamar, and that’s not so sweet—I really should get prepared before he comes back from surgery.

At the bottom left of each patient are pre-written items like “ord lab med note” and “ass” “cht”. These are things that I want to remember to do on each patient, but because I’m so fallible I might forget. “ord” is there to remind me to find time to get up to date on all the patient’s orders (you’d think a nurse would have had time to do that before the shift, wouldn’t you?). “lab”, “med”, and “note” are in hopes that I’ve read through all their labs, medication orders, and notes. “ass” is to remind me of doing the beginning of the shift assessment, and “cht” is to remind me to chart that. I should be embarrassed to say that I need these reminders, but I’m not. There is honestly so little time and so much to do, and so many interruptions, that it can be easy to forget. (There were also many many shifts where I never crossed all of these out, especially on the least sick patients. That’s shameful, but true.)

Looking at that example timesheet now, I’m reminded that sometime before 9, or so, I was concerned enough about edema for Irene in 46 that I wanted to call her doctor (but not so concerned that I needed to call immediately). This shows me that I did make that call around 9:40, and that I charted it and took whatever other actions were needed. Oh, I also see that at the start of shift I noticed that Irene wasn’t wearing the safety risk wristband that she should have; I’m glad I took care of that.

My hospitals had 12-hour day shifts from 7am to 7pm, and night shifts from 7pm to 7am. This timesheet works for either shift, which is why I didn’t use 24-hour time (even though all EHR logging is in 24-hour time).

In summary, if anything needed to be done, and I needed to know that I’d done it (again, memory is not trustworthy), I’d try to get it on this time sheet.

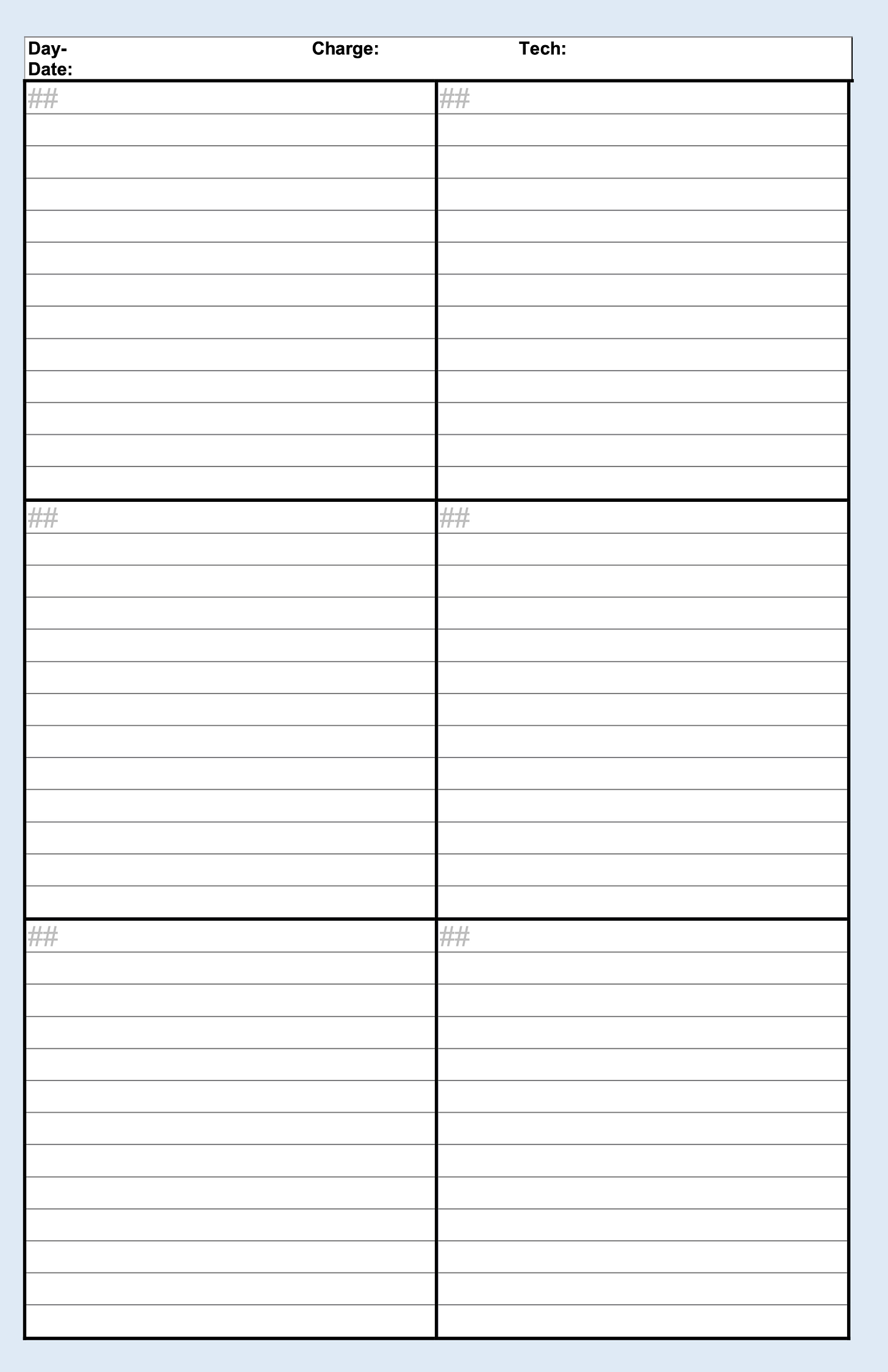

The back of my Time Brain

The Time Brain is double-sided. The back side is kind of boring, with areas to write a few items. I usually use it to keep track of I/O values. For most patients, I write how much they have available to drink at start of shift, how much at end, how much is delivered, and how often there is pee and poop. It’s too boring to say more about now, and this has gone on long enough already, so here’s just a picture of the blank sheet:

Additional Resources

All of the above examples and templates, and their sources (in case you want to change them) are in this online folder: Pocketful of Brains - Resources

I must emphasize, once again, how terrible is the traditional method of patient handoffs. So, see this highfalutin research on nurse handoffs and EHR reports: Why patient summaries in electronic health records do not provide the cognitive support necessary for nurses’ handoffs on medical and surgical units: Insights from interviews and observations. Patients deserve better than what tradition is giving them!

More examples of nursing brains: (everyone is different, find, or create, what works for you):

• Brain sheet Database – 33 Nursing Brainsheets

• Using a "brain" or report sheet

• What’s the Best Nursing Brain Sheet?

Footnotes

Nursing was my second career, after about 35 years as a computer programmer. I chose the switch to nursing because it was about as different from being a programmer as any job I could imagine. Bedside nursing is fast-thinking, on your feet, and service-oriented, while software is slow-thinking, in a chair, and mostly devoid of human interaction. When you’re in software and there’s a crisis, you gather everyone together, call in an order of burritos, and sit around talking about the problem—if you get it wrong you lose a customer’s business. When you’re a nurse and there’s a crisis, you run for the crash cart—if you get it wrong your customer dies.

I consider myself a very good programmer, but only a mediocre (although very hard working) nurse. Maybe in time I could have become much better, but health problems got in the way (that’s what I get for getting old), so one month I took a temporary break to heal. Actually, the health problems have mostly resolved and yet, after almost three years, I’ve seldom felt the urge to go back. That’s what nursing gets for being such a physically, mentally, and morally stressful occupation (if you do it right).

When I imply that I had shifts where I took good care of my patients, I’m lying. I think there was only one time when I ended a shift thinking “I did everything right today”. That was a very good feeling. Every other shift I would fret the drive home from work recalling everything I did wrong or could have done better, and everything I should have done that I never found time to get to, and hoping the patients would be OK despite my incompetence.

When I was a hospital patient, before I started working professionally, I asked one nurse for his most important advice. He said “you must realize that you cannot possibly do everything that you’re supposed to do, and without cutting corners—there just isn’t time. My advice is to understand that you can’t do everything, and to prioritize what is most important in the time you have for the patients you have.”

I was fortunate to experience a variety of hospitals while attending nursing school in California. This let me see how different hospitals, and even different floors within a hospital, operate. I also used a variety (four, I think) of EHR systems.

All of my professional hospital time as a registered nurse was in Florida, where things are a little different than California (lower pay, higher patient loads, non-union, and generally lower standards), and at a single hospital chain (I won’t name the hospital chain, for fear of retribution, but it’s initials are HCA), using their ancient (in computer years) EHR.

My brains may apply best at the particular hospitals I worked in, as some have much better EHRs and procedures. Some hospitals (at least one I did clinicals in) are managed and supplied well enough to not need individualized tools such as these, I just never had the fortune to work in one.

Don’t just take my word for the problems with handoffs, see this research.

Some places have greatly improved upon this archaic handoff system, and even removed the need for making brains such as mine. The general idea is that a card can be automatically generated by the computer system at any time (usually called a Kardex, although that is trademarked), with just the right stuff for a handoff and patient management. The difficulty is in creating a card that has just the right amount of relevant information: not so much that it’s hard to find what you need in a sea of data, and not so little that the nurse must keep scribbling things anyway. Getting this balance right is a fight between the legal and the caregiving aspects of maintaining a hospital.

One of the best solutions I’ve seen was in a hospital unit that had standardized on a paper brain, so that everyone got accustomed to it, and it was the outgoing nurse’s job before the end of the shift to prepare that brain for the incoming shift. During handoff the outgoing nurse could just hand the prepared brain to the incoming nurse, as they introduced the patient and incoming nurse, and would only need to discuss issues that weren’t adequately emphasized by the pre-prepared brain. Very nice!

You must take two fifteen-minute breaks, on a 12-hour shift, and one 30-minute break for lunch. If you don’t punch-in and punch-out for lunch you will hear about it right away (as compared to if you forget to record giving a patient a vital medication, in which case you might not here about that for days, if at all). It is not uncommon for nurses to punch out for lunch, go right on working off-the-clock because they’re so far behind and worried about their patients, then punch back in a half hour later and keep on working. It’s also common, especially for new nurses, to stay 30 to 60 minutes after their shift is over to enter stuff in the computer that they hadn’t had enough uninterrupted time throughout the day to input.

Using different colors from one day to the next, to see changes, is a hint into one major problem I see with some EHRs. This is sort of a niggling issue with me. The problem is in how to interpret the term “record”.

As a verb (accent on the second syllable), “reCORD” means to store information. As a “noun” (accent on first syllable), “RECord” refers to that stored information. In creating my two-colored brain, I am reCORDing, while in looking at it now I am seeing a RECord. Seeing that RECord shows me interesting things about how Tommy’s situation is changing over time.

One problem with many EHRs is their emphasis on the reCORD version of that word. They concentrate on making it very easy to reCORD lots and lots of information. So much information! But they make it much too hard and time consuming to playback the RECord. (The opposite of a phonograph record, which is difficult to create but very easy to playback.) reCORDing reams of information is only occasionally important, in the case of a billing dispute or a courtroom forensic situation, and so it’s good to reCORD as much information as possible to cover your butt. But it’s not important during these occasional proceedings that it takes a lot of time and work to playback the RECord (they’ll have plenty of time to go as slow as they need to to prepare for a court case).

Unfortunately, when you’re in the hospital and the patient isn’t looking too well it suddenly becomes extremely important to be able to quickly playback the RECord.

Alas, when the emphasis is on reCORD, instead of playing back the RECord, the benefit is mostly for the accountants and lawyers, and not for the patients and caregivers.

I imagine a form of EHR where playback of the RECord becomes a priority and is as easy and visual as those flipbooks where there’s an image on each page that you quickly flip through to see an animated movie of events. With an EHR like this, you could see what interventions were made and how the patient and labs changed over time with them. You could witness IVs and other catheters going in a being removed. You could see (both in labs and assessments) patients deteriorating with X, but improving with Y, and you’d see those results coordinated in time with those interventions. However, the systems I’ve used are miles away from this. (I read that Epic has created something along these directions with their Synopsis Activity, but I’ve never seen it in action.)

Over time you get to know which nurses give accurate handoff information and which do not. I recall one nurse, Dunning Kruger (not their real name), who was pretty much wrong about everything, but wrong with confidence! I learned that that everything Dunning said needed to be double-checked, and quickly. Every word of “IV 20G Left AC running LR @ 50” might be wrong: either that wasn't what was happening or wasn’t what the orders said should be happening or both.